“So – what do you do?”

Stumped. I uttered something about “neurodegeneration” and “melanocytes” and “disease models” and the result was faces so blank you could paint a Caravaggio on them.

This scene was repeated several times during my PhD until I learned to just say “biology” and change the subject. It is a common situation that highlights a sad reality: Science is hard on public consumption.

But the times are a-changing. The past two decades have seen a flurry of activity on what we now call ‘Public Communication of Science’. TV, books, columns, blogs; in 2012, science is finally carving out a cultural niche and gaining public interest, appreciation, and respect. We might not have seen white coats spill out into the fashion world, but the demographic is there.

Still, those blank faces still follow any hapless scientist who attempts to explain her work to people who’ve never wielded a pipette, spent days over calculations, or wept quietly over contaminated cells. And stereotypes abound, although they’ve been updated: Gone is the wild-haired, dungeon-working, cackling villain of the ‘50s. Today, Dr Scientist is either a cold, unemotional, “rational” machine that spouts facts and figures, or a socially-challenged, bespectacled geek with perennial food stains on his t-shirt.

Same goes for the public’s trust of science and scientists. Aptly illustrated by Jorge Cham, the purpose of scientific communication does not always coincide with the purposes of media communication. The result has often been needless panic and even more needless criticism of the scientific process. Vaccines, stem cells, climate change, evolutionary theory and the long-suffering LHC all stand as examples of what can happen when research and the media play Broken Telephone.

The need to educate and – yes – thrill the non-scientist public with the scientific effort is still there, but the way of doing it is gradually adapting to its environment: Science is now spilling into two domains that previously were unthinkable means of communication for its doings.

The first is fiction. And we don’t mean science fiction here, which focuses on imaginary scientific impact. Rather, we are looking at a growing body of fiction whose focus is a realistic depiction of scientists and their trade.

The central characters of such ‘lab lit’ novels tend to be normal people living normal lives, with normal abilities and normal weaknesses who happen to be professional scientists. Conflict – the heart of any good novel – is also human: Arguments between lab members. Paper authorship. Data “borrowing”. And although the plots usually draw from the against-all-odds thriller fountain, the scientific challenges facing the protagonists are cast in a real light: Stubborn experiments. Hypothesis-wrecking data. Getting scooped. Elements that, put together, bring to life the arcane and mysterious world of “doing science” in a way that readers can identify with.

Solid efforts have been made in this direction and a growing number of novels are chewing their way into shelves and Kindles. It is an unprecedented phenomenon that reflects a real desire for the non-initiated to see and for the initiated to show. And if The silence of the lambs led to increased female FBI applications, it’s anyone’s guess of what positive effect a lab lit best-seller may have.

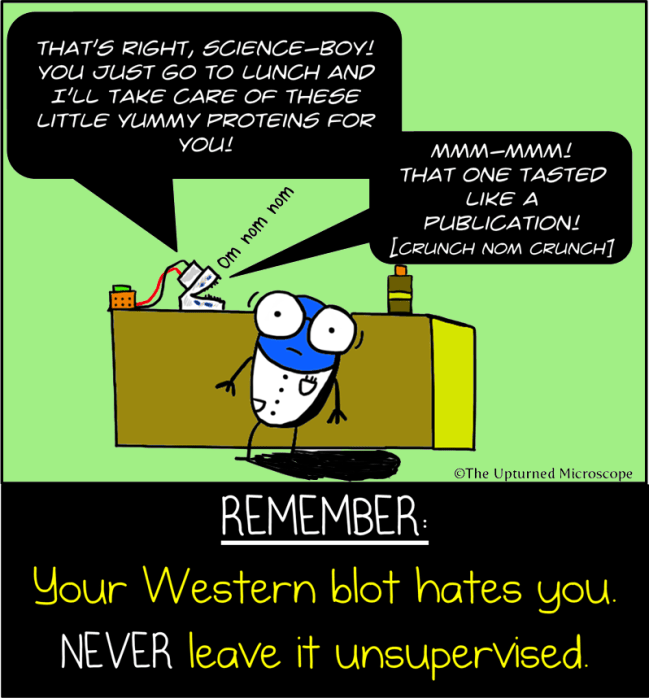

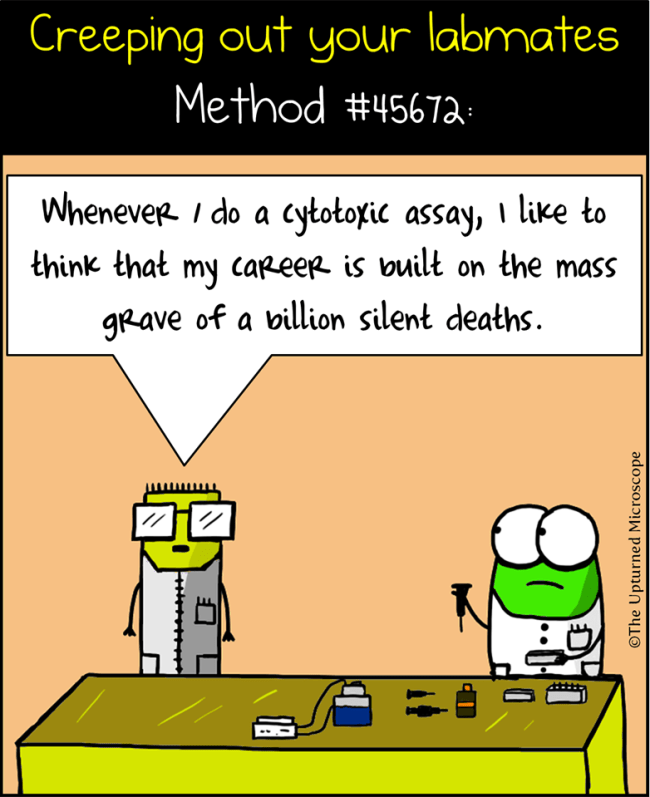

Second comes humour, and this is really the unexpected force. A few years back, ‘science comedy’ would have been seen as a contradiction in terms, like ‘easy PhD’ or ‘ample funding’. Today, the funny bone of science has been well-documented and put to good use. Think of the famous PHD Comics and the hysterical Science Cartoons Plus; that old adage, “an image is a thousand words”, is slowly changing the public perception of scientists as Easter Island-faced robots who run on batteries and facts.

Nor is scientific humour restricted to the graphical. Stand-up is gaining a significant contribution from comedians like Brian Malow and Dean Burnett, bringing an uncanny ability to split sides by splitting atoms. Who knows? There may come a day when “a quark walks into a bar” jokes will be the staple of every good party.

Public communication of science is a concept that seems to be evolving beyond documentaries and pop-science titles. It is engaging the public on both an intellectual and an emotional level, and for that purpose, fiction and humour are practically indispensable.

Some may argue that ‘familiarity breeds contempt’; that pushing science into plots and giggles subtracts from the scientific image and maybe even cheapens it. And it is true that fiction and humour can misrepresent science. When the aim is to excite rather than inform, things can go quickly wrong.

But is that reason enough to keep science shielded from fiction and humour? No. Science cannot exist without some emotion, some passion. In the end, it’s what drives it – and if you want to communicate science to the public, there has to be a place for that.